The interpretation of the 4th Amendment’s guarantee to freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures is particularly difficult in the DNA Age in which citizens may not even know that they are being searched.

A man walking down the street spits on the curb and continues on his way. Soon thereafter two men emerge from an unmarked squad car, lean over the spittle, scoop it into a vile and return to police headquarters with it.

Has the spitting man just been searched? How about if the police officers conduct DNA analysis on the saliva to see if it matches a DNA sample from a crime scene that the officers are trying to solve? A Massachusetts appellate court recently found no problem with the police's conduct.

The DNA Age has presented and will continue to present many novel legal questions that could not have been foreseen by the drafters of the Bill of Rights.

The use of science has benefited both sides of criminal law enforcement. DNA evidence has been used to exonerate more than 200 wrongfully convicted prisoners. These demonstrations of the fallibility of the justice system have also led states such as Illinois to declare indefinite moratoriums on using the death penalty in part because most of the convictions and resulting death sentences were secured without the assurances provided by science.

The prosecution also greatly benefits from DNA evidence. Convictions are all the more likely when science buttresses conventional sources of evidence. It also aids the police in narrowing down the suspects for a particular crime. But how the police obtain the DNA samples is far more contentious than the validity of the results from the samples.

The 4th Amendment guarantees that the people have the right to be secure in their persons from unreasonable searches and seizures, viz., those conducted without first obtaining a search warrant issued upon demonstration of probable cause.

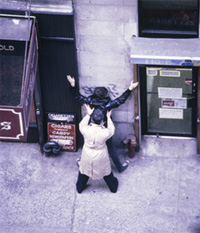

Police officers around the United States have been circumventing the warrant requirement by conducting what has been termed "surreptitious sampling," or the gathering of evidence and subsequent analysis without the suspect knowing he (or his DNA) is being searched.

In addition to whether conducting scientific analysis is a "search" of a person, the legality of the manner in which law enforcement procures the sample is in dispute.

Police are retrieving items with DNA samples in a variety of creative ways including from cigarette butts, drinking containers or even the street as noted above.

There is not a substantial amount of case law pertaining to the legality of these emerging issues but a 1988 Supreme Court decision could be illustrative.

In California v. Greenwood the Court ruled that a suspect did not have a subjective privacy interest in trash that he had encased in opaque trash bags and placed on his curb outside of his home for collection. The Court found that there was no privacy interest because "[Greenwood] exposed [his] garbage to the public sufficiently to defeat [his] claim to Fourth Amendment protection."

Greenwood may illuminate the issue to a degree but trash is not exactly analogous to DNA. Greenwood freely abandoned his trash in public but people do not necessarily choose to abandon their DNA in public. They know they are throwing away a drinking container freely but they may be unaware that they are also leaving their DNA in public. Moreover, even if they were aware of it, interacting in public without leaving some DNA behind-whether it be involuntarily shedding skin or sweating on a hot day-is nearly if not completely impossible.

Establishing a rule in which all expectations of privacy are ceded upon stepping out in public is not a sound policy.

Further analysis from other courts around the country would at least limit the police to collecting the samples only after they have been freely and completely discarded.

An Iowa court ruled that a water bottle taken by the police after a suspect had drank from it during an interview but before he had discarded it could not be used by the police. Also, an appellate court in North Carolina excluded evidence obtained from a cigarette butt that had been kicked off of a suspect's deck by a police officer because the Court found that the suspect had a privacy interest in the butt while it was still on his property.

But even if the police wait for the sample to be discarded, questions remain whether it is pertinent if the sample was relinquished through the officer's inducement. If you only took a drink from a soda can because the police gave it to you, and only discarded the can because they told you do so, have you freely parted with your privacy interest? And should the police have at least some threshold to meet-something less than the 4th Amendment's probable cause standard but at least a minimal good faith demonstration to the judiciary-before tracking, obtaining and testing an individual's DNA?

Some argue that if you are not guilty of anything you do not need to worry about the police having your DNA without probable cause to justify it. Deference to law enforcement is particularly acute in the midst of the War on Terror and overbearing surveillance is shoehorned in and justified by the conflation of crime control and homeland security.

This obsequiousness to government overlooks the potential for misuse of intimate personal information that DNA reveals as opposed to simple identification that is gleaned from the relatively innocuous use of a fingerprint.

Despite this concern amongst others, courts have upheld many incidents of surreptitious sampling as constitutional. So if you are a criminal or you value your privacy, don't eat, drink, sweat, shed, spit or smoke anything in public. Better yet, just stay home.

Associate Professor at the University of Navarra School of Law in Pamplona, Spain